Grass-Fed vs. Grain-Fed Beef: How Do They Compare?

Demand for grass-fed ‘pastured’ beef has increased rapidly over the past decade.

It is also common to hear claims that grass-fed beef is healthier, cleaner, and more humane than grain-fed meat.

However, is it true that grass-fed beef is nutritionally superior?

This article takes a propaganda-free look at the arguments both for and against grass-fed beef.

Note

There are legitimate environmental and animal welfare concerns about how beef is produced.

That said, these issues are beyond the scope of this article, which will focus solely on the nutritional arguments.

Producing grass-fed and grain-fed beef

First of all, most cattle are “grass-fed” for the majority of their lives.

According to livestock experts at Pennsylvania State University, the vast majority of cows spend the first two-thirds of their life feeding on pasture (1).

However, there are some differences in the way in which grass-fed and grain-fed beef are produced.

Grass-fed

Pastured cows are primarily raised on a diet of grass, and they will generally eat hay (dried grass) in the winter (2).

As earlier mentioned, most cattle spend a significant amount of time grazing on pasture, but it is in the final third of their life that some key differences begin to emerge.

For example, many cattle are “grain-finished,” which may mean the cows spend the last third of their life in a feedlot.

A smaller proportion of cattle spend their entire lifetime grazing on pasture, and beef from these cows may be labeled “100% grass-fed”.

Grass-fed beef is relatively common in countries such as Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom.

However, only 4% of cows spend their lives on pasture in the United States, and 96% move to feedlots (3).

Grain-fed

In contrast to grass-fed cattle, grain-fed cows spend the latter portion of their life feeding on grains, often in a feedlot.

The exact grains used for feed will differ by farm and country, but these grains typically include barley, corn, sorghum, and soy (4).

These grains are all high-energy feed options, and they result in increased muscle growth and weight gain in the cows.

For this reason, grain-feeding is preferred by many farming operations due to the enhanced efficiency and profitability it offers. Grain-fed beef also represents the majority of beef produced within the United States (5).

The basic nutrition profile of grass-fed beef vs. grain-fed beef

All beef is nutritious and an excellent source of protein, vitamins, and minerals.

However, there are some small nutritional differences between grass-fed and grain-fed beef.

In the following table, we can see how grass-fed and grain-fed beef compare nutritionally on a per-100-gram basis.

The respective data is for regular (raw) ground beef, sourced from the USDA’s FoodData Central database (6, 7).

| Calories/Nutrient | Grass-fed, ground beef | Grain-fed, ground beef |

|---|---|---|

| Calories | 198 kcal | 247 kcal |

| Carbohydrate | 0 g | 0 g |

| Fat | 12.73 g | 19.07 g |

| Saturated | 5.34 g | 7.29 g |

| Monounsaturated | 4.80 g | 8.48 g |

| Polyunsaturated | 0.53 g | 0.51 g |

| Protein | 19.42 g | 17.44 g |

The above data provides a general idea of the potential nutritional differences between grass-fed and grain-fed beef.

Generally speaking, the key distinction is that grass-fed beef is leaner than grain-fed beef.

However, it should be noted that the precise nutritional values can vary depending upon the feeding regime. For example, the quantity of grains the cows eat and their ability to exercise can both affect the leanness of the beef.

Nutrients and compounds in beef

There are also some specific differences between grass-fed and grain-fed in the concentration of nutrients and other compounds that occur in beef.

Conjugated linoleic acid (CLA)

Conjugated linoleic acid, otherwise known as CLA, is a natural trans-fat.

While the “trans-fat’ name may draw concern, it does not have the same effects as artificial trans-fats, and it has neutral/negative associations with cardiovascular disease (8, 9).

Further, pre-clinical and human trials suggest that CLA may even have a range of beneficial health effects (10).

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials also demonstrated that CLA supplementation might slightly reduce body weight. However, the results were not considered clinically significant (11).

Ruminal bacteria play a role in the production of CLA, which is why we can find CLA in dairy/meat from ruminants (12).

Studies looking at the total CLA content of beef consistently demonstrate that grass-fed beef provides a greater concentration of the fatty acid (13).

Fat-soluble vitamins A and E

Grass-fed beef is a richer source of the fat-soluble vitamins A and E.

Regarding vitamin A, cows feeding exclusively on grass consume a greater amount of carotenoids.

Carotenoids are precursors to provitamin A (retinol), which is the bioavailable form of the vitamin (14).

On this note, studies show that beef from pasture-fed cattle can have up to seven times higher carotenoid content than grain-fed beef (15, 16).

Additionally, grass-fed beef contains significantly higher concentrations of vitamin E.

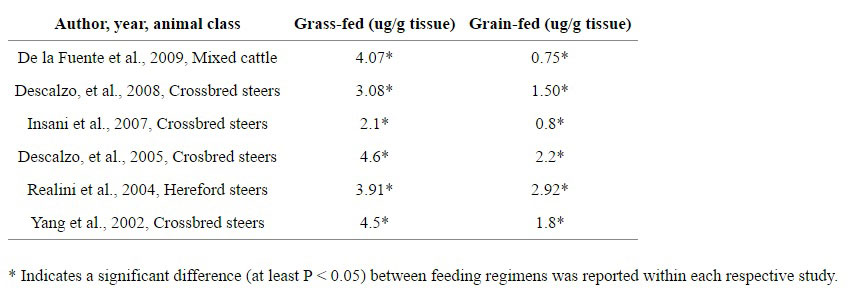

The table below displays the findings of studies that compared the vitamin E content of grass-fed and grain-fed beef (17):

As shown from these results, grass-fed beef broadly provided at least twice as much vitamin E as grain-fed beef.

Monounsaturated fat content (oleic acid)

The predominant monounsaturated fatty acid in beef is oleic acid (18).

For those unaware, oleic acid is also commonly referred to as the “heart-healthy” fatty acid in olive oil.

According to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), there is “supportive but not conclusive evidence” that daily consumption of oleic acid may reduce the risk of heart disease (19).

Mainly due to the fact that grass-fed beef is leaner, it contains a smaller amount of monounsaturated fat than grain-fed beef. This is because the oleic acid content of beef increases with the amount of marbling.

In this regard, a range of studies demonstrates that grass-fed beef has approximately 30-70% less monounsaturated fat than grain-fed beef (20).

Omega-3 content

Meat from grass-fed animals contains a higher amount of omega-3.

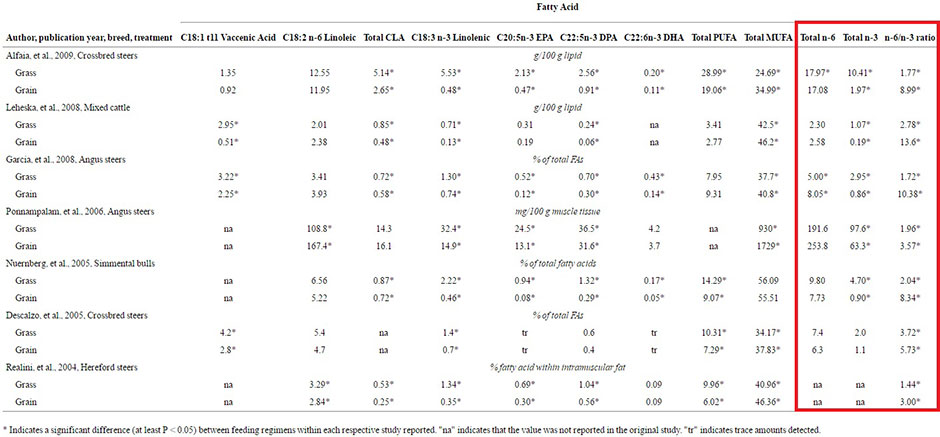

The below data shows the results of six studies investigating the fatty acid profile of both grass-fed and grain-fed beef (21):

As the table shows, grass-fed beef consistently contains a higher amount of omega-3. Additionally, it has a lower omega-6 to omega-3 ratio.

Some researchers believe that the ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 may be important for human health. One of the reasons behind this is that traditional human diets had an omega-6 to omega-3 ratio of around 1:1. In the present day, this ratio is thought to be as high as 20:1 in the average Western-style diet (22, 23).

However, it is worth remembering that beef is not a significant source of either omega-3 or omega-6. Beef mainly consists of saturated and monounsaturated fat; it contains only 0.5 grams of polyunsaturated fat per 100 grams (5, 6).

Taste

Grass-fed and grain-fed beef have a different taste, and we can attribute a lot of this to the varying levels of fat and marbling between the two.

Generally speaking, fattier cuts of beef are more prized, and we can see an example of this with Japanese Wagyu.

Wagyu has exceptionally high levels of fat/marbling, and this is a significant factor in why it tastes good.

In short, many people prefer the taste of fattier cuts of grain-fed beef. This assertion is supported by palatability panel scores that see grain-fed beef significantly outperform grass-fed beef (24).

Grass-fed beef may not be as tender as grain-fed beef due to the (typically) lower fat content.

Additionally, grass-fed beef tends to have a stronger and “meatier” flavor similar to other leaner meats such as bison and venison.

Is grass-fed or grain-fed beef the better choice?

Overall, both grass-fed and grain-fed beef have benefits and drawbacks.

Based solely on the nutrition profile, grass-fed beef is slightly superior due to its higher vitamin and CLA content. It is also more protein-dense.

However, the differences are only small, and all types of beef offer good nutritional value.

It is also worth considering the price; grass-fed beef typically costs around 30% more than grain-fed beef.

Affordability and taste preferences are just as relevant as the nutritional profile too. Therefore, the superior choice is the one that best meets the needs of each individual.

For more on meat, see this guide to the benefits and drawbacks of red meat.

7 thoughts on “Grass-Fed vs. Grain-Fed Beef: How Do They Compare?”

But what about the phytic acid, lectins and other toxins from the grains? Aren’t they found in the grain fed meat? I know that many people avoid getting the grains substances second hand, when they try to avoid all grains fed meat.

As I understand it, the feed can sometimes cause issues for the cows (e.g. digestive issues), but you won’t find those things in the actual meat. One historical issue, in the United States at least, was the higher likelihood of the over-use of antibiotics due to some farming operations prioritizing quicker growth. That should have been solved by the new FDA law prohibiting antibiotic use for general production purposes: https://www.fda.gov/animal-veterinary/development-approval-process/fact-sheet-veterinary-feed-directive-final-rule-and-next-steps Other than that, it’s really about the slight nutritional differences/taste/cost considerations.

Thank you, Michael. I hope you are right. It is certainly not what the paleo teachers say.

That was an extremely helpful analysis. I buy beef from local farmers and usually it’s grass fed. Buying local remains more important to me than whether it’s grass fed or conventional.

Glad it was helpful, John. I agree that buying local food is one of the best things we can do, and I’m sure it’s better for the environment too.

Nice article. Any thoughts on antibiotics accumulating in the fat of grain fed cows due to the higher amount of body fat and being passed on to the consumer?

It does seem that this may have been an issue in the past, particularly in the United States. However, new laws were introduced by the FDA in 2017 that prohibited the use of antibiotics for growth promotion in animals. Since then, they can only be given if signed off by a veterinarian as being used for genuine illness. Since that time, FDA data shows that antibiotic use has significantly dropped.

You can read about that law and the corresponding decline in use at the following links:

1) https://www.fda.gov/animal-veterinary/development-approval-process/fact-sheet-veterinary-feed-directive-final-rule-and-next-steps

2) http://www.cidrap.umn.edu/news-perspective/2018/12/fda-reports-major-drop-antibiotics-food-animals

Comments are closed.